The growing $1.1 trillion student debt burden in the US has been well documented, yet concerns are subdued. That’s because the burden, unlike the housing crisis, won’t cause a sudden economic crash. Instead, it will prompt a slow strangulation of spending spread over many years. Congress has made some minor efforts to reduce interest rates on debt, but the necessity for such large loans must be scrutinized. And that means confronting the indulgences of colleges.

The growing $1.1 trillion student debt burden in the US has been well documented, yet concerns are subdued. That’s because the burden, unlike the housing crisis, won’t cause a sudden economic crash. Instead, it will prompt a slow strangulation of spending spread over many years. Congress has made some minor efforts to reduce interest rates on debt, but the necessity for such large loans must be scrutinized. And that means confronting the indulgences of colleges.

Tuition costs have soared in recent decades. In 1973, the average cost for tuition and fees at a private nonprofit college was $10, 783, adjusted for 2013 dollars. Costs tripled over the ensuing 40 years, with the average jumping to , 094 last year. Even in the last decade the increase was a staggering 25 percent.

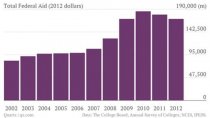

The ability of colleges to raise costs has been facilitated by a sharp increase in federal student aid. Lenders freely dispense credit to students, safe in the knowledge that all loans are guaranteed by the government. Between 1973 and 2012, federal aid (inflation-adjusted) increased more than 500 percent. Looking at a shorter period, between 2002 and 2012, total federal aid to students ballooned an inflation-adjusted 106 percent to $170 billion.

Colleges have effectively been guaranteed an income stream and have used that certainty to partake in an arms race against each other by constructing lavish facilities and inflating administrative processes. The pursuit of education has turned into a vicious circle in which students need bigger loans to pay for higher costs, and colleges charge higher costs because students are getting bigger loans.

The apparent escalation in college bureaucracy may be reflected in changing patterns of teaching hours. A national survey conducted by the Higher Education Research Institute found in 2011 that 43.6 percent of full-time faculty members spent nine hours or more per week teaching (roughly a quarter of their time), which is a down from 56.5 percent in 2001 and a considerable decline from a high of 63.4 percent in 1991.

Notably, hours spent preparing for classes fell at a similar rate, while there was little change in time devoted to research. Administrative bloat fueled by excessive spending seems to be diminishing the focus on what college is supposed to be about, with the study showing that almost a quarter of professors at four-year universities do not consider teaching their “principal activity.”