Latin America’s education challenges call for concrete action

Latin America’s education challenges call for concrete action

Tamara Ortega Goodspeed

Photo: Michael Lisman, PREAL, Inter-American Dialogue.

Youth in the classroom of a rural multi-grade primary school in Zambrano, Honduras, November 2007.

Latin America’s education systems suffer from low levels of learning, limited opportunities for the poor, bureaucratic paralysis and chronic conflicts with teachers’ unions. The solutions are neither magical nor beyond human capability: taking action to establish standards of performance and quality, improving the teaching profession and increasing spending for the neediest are key to ameliorating education in the region.

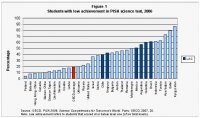

Schools in Latin America clearly need a serious overhaul. Although enrolments at every level are increasing, most children receive poor quality education. On recent international tests of mathematics and science, roughly half of Latin American students scored at or below the lowest proficiency levels, indicating that they had difficulty applying basic concepts to real life situations. By contrast, only 10 per cent of students in Finland and an average 20 per cent of children in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries scored at this level (see Figure 1).

Education is also highly unequal. Despite growing access to primary school, poor children in Latin America are roughly half as likely to enrol in pre-school and two to 10 times less likely to graduate from upper secondary as their richer peers. Students from poorer families also score lower on tests, between one to two proficiency levels lower on the OECD’s 2006 Programme in International Student Achievement (PISA) science exam than those from higher income families. Indigenous and Afro-Latino children also remain at a disadvantage.

Poor management makes the problem worse. The structure of the teaching profession —from recruitment to training to management— does not foster excellence. Students entering teacher training are seldom among the best of their classes, courses are often deficient and the best teachers are too rarely assigned to poor students who need them most. Moreover, it is nearly impossible to remove ineffective teachers from the classroom. Frequent clashes between teachers’ unions and governments that result in strikes, such as those in Honduras and Nicaragua, continue to cost students precious days of instruction.